Where the Rubber Meets the Road

A MEV-Aware, Functionalist Review of OFAC Risk "on the Base Layer"

It’s only been a half-year (seven ages, Crypto Time) since the United States Office of Foreign Asset Control (“OFAC”) shook the blockchain industry by sanctioning free, open public software—tooling that persists online, autonomously, without any necessary human intervention, owing to the rough consensus of a network of self-motivated blockchain validators—for the offense of being used by North Korea to launder money, ostensibly for nuclear weapons.

Soon thereafter, respected crypto-natives released forceful defenses of so-called “base layer neutrality,” or the notion that neutral blockchain infrastructure providers (e.g., Ethereum’s searchers, builders, relays and validators / proposers) should be treated like their messaging analogues in the modern telecom and trad-financial sectors. The crypto industry speaks of these infrastructure providers, collectively, as “the base layer” of Ethereum, but I don’t believe the homogeneity of that term serves us. I instead prefer to refer to these actors as distinct members of a broader class that I call “block-building participants” (“BBPs”), distinguishable by the functions they perform on the block-building and -recording assembly line, as explored more below.

While the industry’s policy positions on this issue have been well-meaning and strongly argued, particularly given the expedited timeline in which they were produced, I must respectfully disagree with the interim guidance potentially drawn therefrom, that all U.S. BBPs need not monitor or censor Tornado Cash (“TC") smart-contract addresses as part of a risk-based OFAC sanctions compliance program.

There are rarely one-size-fits-all solutions for the disparate actors in this space. It is only prudent to explore the landscape with a bit more granularity, particularly where avoidance of regulatory scrutiny depends on the self-determined line-drawing of the hopefully-compliant. Herein, I hope to provide a novel synthesis of legal, political and technical perspectives that accurately reflects today’s fast-evolving and oft-overlooked BBP sphere. A comprehensive understanding of these issues may prove important for developers working in this micro-niche (and their advisors) as they seek to avoid lawsuits and costly macro-strategic mistakes.

Limiting industry best practices to simply assuming that the government will agree that BBPs are neutral (and free to disregard OFAC) may expose certain of them with a U.S. nexus to greater risk than expected today. This risk arises from their capture of Maximal (prev. Miner) Extractable Value (“MEV”). The means by which block-building is really accomplished in this MEV Era of 2023 Ethereum could be seen by politicians, OFAC and courts—acting in a wartime posture with respect to North Korea—as being operated illegally by certain “controlling facilitators” of sanctioned “property”: uncensored U.S. searchers and builders, as well as proposers applying similar individual discretion.

While technological developments are underway to remove self-interest throughout the block-building chain, credible neutrality “on the base layer” (and thus the alleviation of monitoring and filtering duties that, I agree, it should bring about) has not yet been defensibly achieved. A dual-pronged approach of both protocol and legal design and engineering should be employed by those in the BBP sector to maintain strategic regulatory compliance, while technical solutions are brought to mainnet to fortify BBPs’ legal and political stance, as well as the core protocol’s resilience.1

1) What

A brief recap of how we got here is called for. On April 1, 2015, pursuant to powers delegated him under, among others, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (the “IEEPA”), President Barack Obama signed Executive Order 13694 (the “Order”), granting OFAC the authority to add foreign cyber-offenders to its Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List, the sanctions register on which the TC addresses sit today (the “SDN List”). Notably, the Order and related guidance bar “deal[ing] in” (or “facilitating” dealings in) the “property and interests in property” of “persons” on the SDN List which “come[s] within the possession or control of any United States person.” We’ll examine these key terms in more depth below.

After Obama left office, in December 2019, the decentralized anonymization application Tornado Cash was first shipped by its developers to Ethereum mainnet. Ever since, its passive, immutable code has been available for use by anyone with an Internet connection, no dev or DAO upkeep required. Consider the functions humans perform to make that happen: end users offer fees to validators to change Ethereum’s chainstate in accordance with the inert smart-contract logic being called (here, TC’s).

Among the many that utilize(d) mixers for basic privacy-preservation on the otherwise transparent and traceable Ethereum chain, one unsavory network citizen, the Lazarus Group (North Korea’s cybercrime arm, infamous for a decade of high-profile hacking), permissionlessly leverages TC to conceal its ill-gotten gains (or at least to attempt to). On August 8, 2022, in light of Lazarus’s enduring success and impunity, OFAC—seemingly bereft (and/or unaware) of further mortals to target, and under pressure to act—took the unprecedented, unclear and potentially unlawful step of sanctioning TC’s mere code itself.

In the immediate aftermath of TC’s listing, Coin Center sued OFAC, claiming in part that the SDN List is restricted to “persons,” so software falls outside its scope. Coinbase also announced that it was bankrolling a lawsuit by six former TC users, further challenging OFAC’s authority by arguing in part that TC’s immutable smart contracts cannot be “owned” by anyone, and are thus not “property” that can be SDN-listed. The complaints led to a hasty redesignation of TC by OFAC, reflecting a need to revisit this action, rushed to release by NatSec officials in the Administration.

dApps like Aave quickly enlisted chain-analysis firm TRM Labs to screen wallets with, in their estimation, intolerable TC exposure, and premier BBP Flashbots (a DE LLC) made the much-pilloried decision to extend its existing practice of filtering SDN-linked transactions from its blocks. After an early spike in such “weak censorship” by BBPs, several factors have led to its plateauing, then steady decline through today. The fervor on Crypto Twitter has died down in recent months, but the dilemma that sparked the initial panic remains with many U.S. crypto orgs, torn between a philosophy of open software and the natural aversion to personal legal liability.

Comparing Oranges and Napalm

To better contextualize these more worried (and worrying) reactions, it’s important to understand that the risks cryptoactors face from these sanctions could escalate in severity much more easily than those which form the basis of crypto’s struggles with, say, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”).

The SEC and OFAC both largely enforce civilly, though each has the ability to refer more egregious violators to the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) for criminal prosecution. Where the SEC ropes in DOJ, there is typically outright fraud, a charge that requires demonstrating the hard-to-prove mental state of scienter (realities which Sam Bankman-Fried seems to be conscious of). On the other hand, OFAC’s regs carry a “strict liability” standard (i.e., no requisite mental state to argue over), and it has only chosen to reserve enforcement for willful or reckless behavior. As such, many SEC questions are based on differing legal contentions over the limits of its authority (i.e., “can it…?”), while the uncertainty with OFAC is whether/when it will deign to exercise power that it’s much more likely to already have (i.e., “will it…?”).

The distinct policies underlying the respective regulations here, I’m afraid, further demonstrate how much more likely this latter Sword of Damocles is to fall. In non-fraudulent investment arrangements, where the harmed can theoretically be made whole and risk is largely confined to volitionally-involved individuals, the harmooor can’t so easily be deprived of their constitutionally-protected liberty, and citizens retain more tools with which to combat SEC overreach. However, on the geopolitical stage, as between sovereigns (particularly two under armistice), the power dynamics at the heart of “international law” give the world-leader U.S. far more flexibility, which also often loosens its constraints back home and entertains much less pushback.

Crypto is clearly a top SEC priority—to divine what could shift OFAC to behave more aggressively and make use of its latitude, one might look to the agencies’ driving motivations. SEC Chair Gensler has assumed a prominent, personal role in a crusade against what he’s declared to be a pressing mass violation of laws that his agency has a stated mission to uphold. Meanwhile, with a hot war in Europe, OFAC’s attention is elsewhere as the U.S. National Security Council inundates it with demands. When one compares the impact of a nascent industry whose aggregate market cap is less than that of a single tech giant, with a horrific yearlong conflict and its six-figure death toll, it’s evident that OFAC has bigger fish to fry than Tornado Cash.

That said, although it may be preoccupied (even overwhelmed) with Russia/Ukraine, OFAC is not stupid. Having run the gauntlet of designating TC, being summarily flamed and sued, and then re-designating TC, the topic is irrevocably on its radar. I understand that OFAC officials maintain a great interest in BBPs, actively researching their varied roles with shrewd skepticism over whether they are simple routers, or “controlling” intermediaries. Imagine what may happen if/once their desks are cleared of Russian affairs, and North Korea gives these seasoned operators (or the lawmakers that impel them) new reason to revisit the intensity of OFAC’s blockchain oversight.

From a pragmatic perspective—the perspective Prof. Brian Frye has argued we should maintain with respect to the SEC’s jurisdiction—one must recognize that OFAC has broad authority as an arm of the U.S. foreign-policy apparatus. OFAC and DOJ likely won’t hesitate to exercise it when one of the empire’s most sworn enemies is the concern. As shown further below, the relevant legal language may create enough of a loophole for courts, in the service of the Commander-in-Chief, to find (and/or expand) cover for an offensive on Ethereum’s critical infrastructure beyond what many might anticipate.

MEV: The Hidden Hook

Before we, at last, dive into the text, we must define MEV for our purposes. To the extent that there is a coherent definition, the term “MEV” might generally be used today to characterize:

the sum total of all economic value that could be / is captured by the various third parties performing a public blockchain’s block-building functions (i.e., BBPs), enabled by their privileged access to and control over transaction flow and ordering, prior to such transactions’ inclusion on-chain; and/or

the strategic means of capturing such value.

Some MEV techniques, like arbitrage and liquidation, benefit ecosystem health by, respectively, keeping cross-exchange prices tightly correlated and eliminating “bad debt” from liquidity protocols. By contrast, so-called “toxic” MEV describes more predatory measures, all which serve to enrich BBPs at the expense of the market.

The most prominent example of toxic MEV is the all-too-common sandwich attack. There, an attacking searcher targets a third-party swap transaction by “bundling” it in between its own frontrun-buy and backrun-sell transactions (🥪), assembling an atomic chain of state-changes that no other user can wedge its orders amidst. The new leading buy order increases the market swap price for the attacked user (Value effectively lost by the user), whose immediately-succeeding attacked swap further pumps the price. The attacker then enjoys an artificially inflated market into which to sell its just-bought tokens for a profit, via the new trailing sell order: Value thus “Extracted”. A few more examples of toxic MEV are included at this footnote:2

In an effort to fashion a more formal taxonomy of toxic MEV (and to retain some substance in the meme, after The Merge eliminated Miners as BBPs), Flashbots researcher Xinyuan Sun has proposed parsing MEV into three subcategories. Each corresponds to the discrete credible-neutrality failure giving rise thereto:

“Mafia” Extractable Value, captured when BBPs have “asymmetric knowledge of another agent’s private information” (e.g., sandwiches, generalized frontrunning);

“Moloch” Extractable Value, captured or lost due to suboptimal coordination (e.g., externalities, like spam, arising from the implementation of random or naive-first-come-first-served preference-ordering mechanisms by block-builders, or from the high-frequency-trading arms race on Wall Street); and

“Monarch” Extractable Value, captured by privileged coordinators (e.g., validators and sequencers) in their ability to gatekeep / profit off of how blockspace is used.

Sun’s “3EV” framework is constructive, as it concretely ties the goal of eliminating MEV to that of achieving credible neutrality and, it follows, an uncensored Ethereum. He charts a “0% / 0% / 100%” endstate, where MafiaEV and MolochEV are eliminated by advances in technology, and the remaining MonarchEV is distributed back to the chain’s end users, all undergirding Ethereum’s neutrality. In rightfully tagging frontrunning as MafiaEV rather than MonarchEV, 3EV also reveals that there could be much less MEV to reallocate in Sun’s ideal world. Directly neutralizing each 3EV source—as the engineering reviewed below seeks to do—would thus bring BBPs closer to the mere routers that OFAC abides and lend industry politicking new legs.

On Ethereum today, at least four specialized BBPs make up the block-building chain: searchers (and their future intermediaries), builders (and their future sub-actors, and layer-2 sequencers), relays, and validators / proposers. As explained more below, each of these actors performs a critical—if at times discretionary—function in Ethereum’s block-building process. Because of the discretion they exercise over MEV, at least some BBPs may be targets for charges that they have violated OFAC regulations.

The growth of MEV and, consequently, the proliferation of these profitable and targetable roles are byproducts of the vast crypto-economic game that arises when markets like Flashbots MEV-Boost (detailed below) are established to split up those functions necessary for the propagation of Ethereum’s financial-order messages, which are often consolidated (and abused) in traditional finance.

An arguably-unavoidable appendage of decentralization, MEV changes the risk calculus for BBPs relative to predecessor-tech operators. As noted above, OFAC polices financial flows through entities with “control” over sanctioned “interests in property,” and MEV—the systemic reapportioning of value out of crypto’s such flows—may provide them a novel hook to latch onto. We gloss over it at our peril.

Don’t Fade the Feds

In that spirit, we’ll take another spin through the legal argumentation surrounding the TC sanctions, this time from OFAC’s plausible MEV-aware perspective. As a refresher, the full legal-linguistic question here is essentially whether BBPs could be held to be “facilitating / dealings in / controlled / interests in property / of a sanctioned person” by building or proposing blocks containing TC transactions. In an effort to steelman the worst-case scenario, I may interpret questions of fact in OFAC’s favor here. I will return to expand upon such facts through the tech further below.

On “control,” in the absence of a controlling definition for the word within the IEEPA, the Order or the TC sanctions, we are left with the canon that a common understanding should prevail, far widening the range of interpretations. Black’s Law Dictionary defines “control” as requiring “holding property in one’s power” or “the power to ‘govern’ or ‘manage’ the property.” However, even that same definition has an alternate reasonable read: “the power … to … direct, or oversee.” Isn’t that the power BBPs have over the orders flowing through their markets, as demonstrated by the examinations of toxic MEV and 3EV above? Even without an exhaustive survey of definitions, it’s safe to say OFAC may have passable claim and shouldn’t yet be counted out here.

But what exactly do BBPs have such control over? Does it amount to an “interest in property”? Unfortunately, the existence of MEV seems to prove that BBPs are in control of a beneficial interest in the property that they “deal in” by reporting transactions. In other words, while a BBP may be unable to “block” the property underlying the transactions it reports, by capturing MEV (i.e., redirecting such value out of the market and into its pocket), doesn’t it de facto show that it controls some economic interest therein? Top litigators might argue that a pro-BBP interpretation should be applied in light of this ambiguity, per the Rule of Lenity, but that’s hardly any guarantee to hang one’s hat on.

I appreciate the cunning of the Coinbase-backed plaintiffs noted above, who have argued that TC’s permanent and unchangeable code cannot be “owned" and thus is not “property” at all, but I find their likelihood of success there dubious. It would be quite tough to convince a court that software (i.e., intellectual property) can morph into being wholly outside the realm of property, simply by being on a blockchain. Indeed, while the claimants’ motion says that no one has the “right” to “alter … delete … [or] exclude another person from using” TC, that is not literally true. A sustained 51% attack on Ethereum, blacklisting an array of validators from having their blocks attested to, could be argued to accomplish “exclusion” thereof from TC. One could also imagine a civilization-altering event like an EMP-weapon attack that destroys the physical backbone of the Internet “deleting” TC. While these are certainly extreme examples, it may only take one flaw to defeat the likewise extreme position that IP is no longer regulatable property (and not collectively “owned” by the Ethereum validator set, etc.).

“Facilitation” has been the cause of much consternation in this debate. One can sympathize with the concern given how this supra-regulatory gloss—issued in more informal guidance—expands the scope of OFAC’s authority so substantially. Leading experts have noted that it is so expansive as to include “all instances … [of] ‘assist[ing]’ or ‘support[ing]’ … transactions … indirectly involving” an SDN-listed party. Consider whether BBPs could be found to clear that low bar, as we dive into their functions below. The term probably deserves its own comprehensive jurisprudential study, but suffice to say that, after factoring in MEV as we’ve come to understand it, it becomes much tougher to claim that BBPs are acting today in a “purely clerical” fashion “that does not further … financial transactions,” which OFAC has carved out of “facilitation” in past, lapsed regulations.

Lest you lose all hope, we’ll draw down this section with some more positive news, first with the final “person” element. While it is not novel for OFAC to sanction Ethereum wallets (including Lazarus’s), what is unprecedented is that TC’s addresses point to autonomous smart contracts which cannot alter chainstate themselves, not to “EOAs” which are owned by any individual or entity (not even TC’s DAO). Coin Center’s lawsuit and Paradigm’s leading policy paper correctly highlight this fact, and I cannot reasonably disagree. This angle of attack represents one of the stronger means of challenging the TC sanctions, at least prior to OFAC’s redesignation thereof.

There is also supplemental statutory language in effect that adds to BBPs’ case for a carveout from OFAC’s purview. The 1988 and 1994 Berman Amendments to the IEEPA exempt “the importation … [of] any … informational materials,” “regardless of format,” from regulation or prohibition thereunder. However, OFAC has sought to limit this promising beachhead for BBPs as inapplicable to “informational materials not fully created … at the date of the transactions … includ[ing] … provision of services to … assist in the creation of … informational materials.” These exceptions-to-exceptions might land us back in the same place, with MEV providing OFAC enough fodder to get a judge to agree that the text is on its side.

The federal court case following the White House’s previously attempted TikTok ban arguably shows that courts are sympathetic to limiting OFAC along these lines. While true, this is where the above discussion on the toothlessness of “international law” could become most salient. Again, North Korea’s status as a U.S. military foe makes it much more likely that combatting its nuclear program could take priority over reasonable technicalities to the contrary, in ways that fighting the more attenuated harm of Chinese datamining may not warrant. There may be some potential here for BBPs that merits its own extensive scholarly review as well.

Should a BBP find itself in court defending its side of the above, I’ve saved my most nagging self-criticism for last: there is no MEV in a TC transaction itself! Interacting with TC requires only simple deposit and withdrawal transactions, i.e., there is nothing to sandwich or other 3EV to extract. The actual Value being Extracted doesn’t come from end users of TC, but rather from a particular trading market at large (e.g., the collective of LP-token holders for an applicable AMM pair). One may argue this nuanced point: that, without any MEV in the actual sanctioned property, MEV should not play into OFAC’s analysis of BBPs. On the other hand, a court could still decide that MEV capture shows broad BBP control over block contents, per above, so even if a certain transaction itself doesn’t have MEV, control thereof is nonetheless imputed, and BBPs’ “assisting” in its propagation equals “facilitation” of “dealing in” sanctioned “interests in property.” Unfortunately, a defendant may have to face down charges before we find out.

In the American legal tradition, laws are truly “made” through the iterative interpretation of statutes and regulations by courts in the cases brought before them. At trial, lawyers vie to convince judges that their respective constructions of the applicable governing texts better exhibit the principles and rules that our learned legislators intended to embody therein. That is, we don’t really know what the law is until after someone gets sued. It is often said that “bad facts make bad law,” and given that OFAC’s strict-liability regime carries fewer elements to satisfy, those facts that remain germane bear more relative weight. In circumstances like ours—where interpretation of such facts could go either way—any unforced error could set us down a precedential path that would be much harder to retread later.

Regardless of your read, still ask practically: what if Coin Center and others succeed, and it remains unlawful to sanction pure code? Will OFAC be deterred, with TC calls still achieving finality? Or, what if OFAC wins the cases, the judicial branch deferring to the will of the Executive in martial affairs? Could this invite a fuller assault, led by fresh charges that some boastingly non-censoring, MEV-enjoying U.S. BBP “facilitated” TC transactions? In the long-developing tension between government fiat and this antifragile technology, this may be (you guessed it!) Where The Rubber Meets The Road. Mindful of the stakes, the sides and the state of play, each BBP must analyze its unique circumstances to craft a holistic compliance approach.

Toward Functional Neutrality

While I’m on board with the core proposition that neutral transmitters of public communications data—whether over the phone lines, across fiber optic cables or onto a blockchain—should not be responsible for monitoring traffic on their rails, I have concerns, like Vitalik’s, that Ethereum is not ready for that kind of prime-time scrutiny. In this imperfect present, as with the environment giving rise to crypto’s “sufficient decentralization” quagmire in SEC-land, it’s clear that certain BBPs exercise more self-interest than others (vis-à-vis MEV, as shown just below). We’d expect their OFAC risks and their corresponding responses to vary accordingly.

In a way, Ethereum is a victim of its own parabolic success: such a desirable, open platform as to attract sufficient liquidity for state-level mixer use, but not mature enough to deflect all resultant regulatory heat. Protecting this vital communal infrastructure during its vulnerable adolescence therefore needs to be dual-pronged:

Continued core development to further the progress of Ethereum along its roadmap; and

Purposeful operational measures to provide defensible legal cover in the interim.

The latter strategically manages risk, utilizing “strength in numbers” and weakening OFAC’s arguments that one’s actions were askew relative to its express expectations. The former (i) steadily diminishes the “recklessness” of (i.e., risk in) abandoning such measures; (ii) could strengthen the industry’s footing in a Berman Amendment counteroffensive; and (iii) represents the only path to convincing D.C. to resolve this existential threat for good. Now, let's get technical:

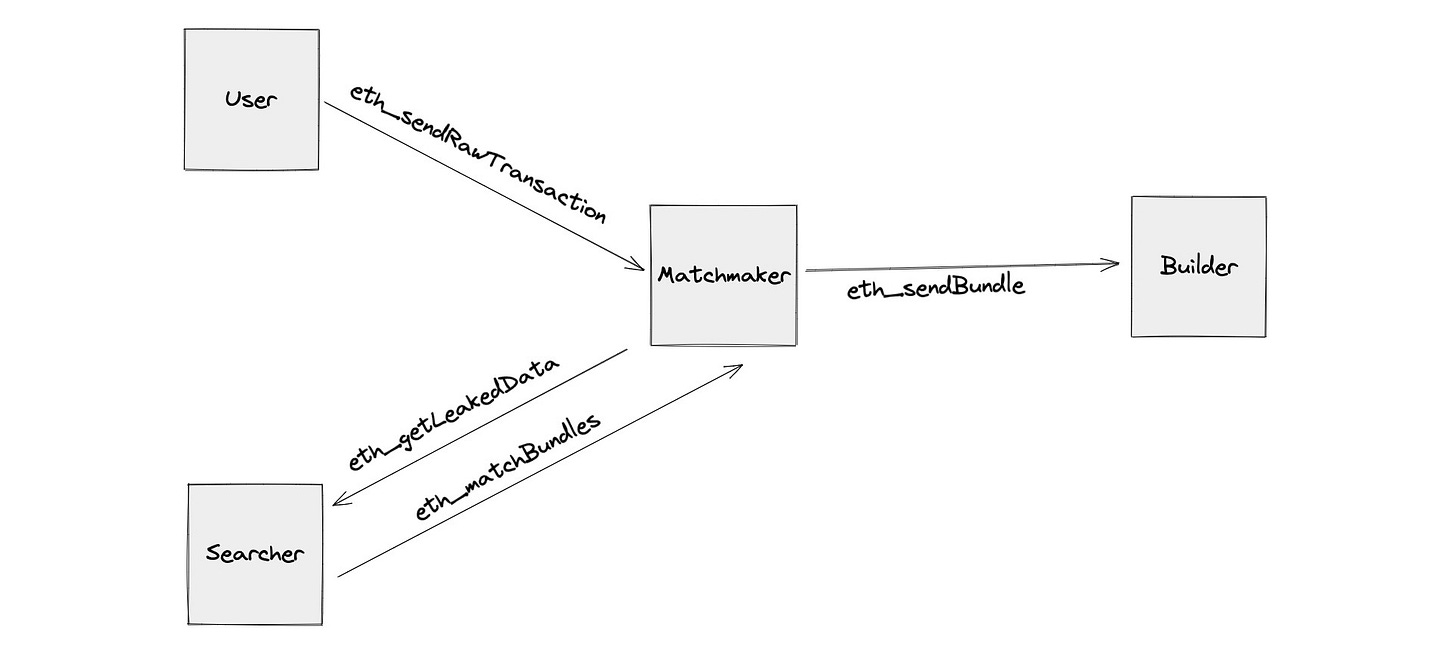

N.B.: We’ll be reviewing the Flashbots Auction’s takes on Proposer-Builder Separation and Order-Flow Auctions, the leading designs and implementations on the market today. The relevant BBPs are broken down in the diagrams below, originally prepared by Flashbots. This essay is limited to mainnet Ethereum, as of Q2 2023. There are myriad other permutations of MEV throughout crypto. I look forward to digging into them more at a later date.

Searchers

Functions:

Thankfully, unlike some areas of crypto, actors’ names in the Flashbots marketplace cleanly map onto their functions. Searchers, as the name suggests, search for MEV by monitoring the blockchain and related data—the mempool of pending transactions, off-chain sources like centralized-exchange order books, etc.—and bundling together orders (others’, and often new ones of their own) to realize the MEV laden within.

As noted above, examples of toxic MEV techniques employed by searchers include sandwich attacks, as well as more “long tail” methods—like NFT “sniping” and one-off event-driven bounties—which require increasingly more research time and developer sophistication to identify and execute upon prior to other hungry searchers.

Searchers may serve multiple roles, simultaneously as builders or providing other services like RPC gateways (e.g., in a wallet interface). However, when they’re acting in their capacity as transaction-bundler, we’ll refer to them, functionally, as “searchers.”

MEV Capture:

Searchers are the front lines of MEV, as they work to convert MafiaEV (and some other 3EV) from its potential to kinetic state. However, although they do much of the legwork in manifesting the MEV, presently they’re driven to give most of it away.

The proto-Flashbots crew made evident that there were millions in MEV out in the open for a searcher in 2017. Ever since Flash Boys 2.0 kicked off the “illumination of the Dark Forest,” though, crypto’s open-source culture has naturally resulted in very high competition on the most basic MEV, like uni-domain arbitrage. This has caused a race to the bottom for these easier opportunities, driving margins razor-thin as less-sophisticated searchers undercut one another, trying to convince builders to choose their bundles as the most profitable for them and other BBPs further down the chain.

OFAC Risk:

Though searchers may have to watch their backs from competitors, their business practices are less impacted by all of this OFAC analysis. Searchers are in quite a black-and-white situation with respect to the sanctions, in that they can simply choose not to actively include TC transactions in the bundles they compile and pass to builders.

This may cause a philosophical dilemma for the searcher, but this form of participation in censorship is unlikely to materially affect its bottom line. As noted above, there is little MEV to draw from TC deposits / withdrawals themselves, meaning that searchers could likely keep capturing the same MEV they always have.

Those searchers not necessarily prioritizing their profits and instead concerned with the long-term censorship-resistance of the ecosystem may be eagerly anticipating a range of tech that seeks to encrypt the mempool. Whether by “shutterizing” it or implementing long-term upgrades like verifiable delay functions, there are several in-development solutions and other research questions for reducing pre-block-proposal information asymmetries, rendering frontrunning of all sorts nigh-impossible.

Using the 3EV framework, one can see that eliminating these sources of toxic MEV (i.e., all MafiaEV), brings Ethereum significantly closer to credible neutrality and, by extension, no censorship. With the order-flow auctions (“OFAs”) that we’ll turn to next, searchers could be further incentivized to return any MonarchEV they produce to the users first generating it, bringing us further toward a “0% / 0% / 100%” world.

Inter-Searcher Matchmakers

Functions:

Flashbots only recently announced this role to power their newest planned product, MEV-Share: an OFA designed to give MEV back to the users that generated it. On April 20, 2023, Flashbots released a beta version of MEV-Share, accessible by Ethereum end users through the Flashbots Protect RPC. Flashbots generally explains that matchmakers receive user transactions and pass along select data therefrom which users opt to reveal to searchers, who then send back bundles compatible with such unhidden data. Matchmakers ensure MEV is indeed paid to users by inserting “validity conditions” in bundles, requiring that builders pay such “kickbacks.”

Though an intriguing platform design, there are still many tricky details to be ironed out, like how best to enforce such validity conditions and how much MEV optimally can be returned to users. Though the present beta release is closed-source within their RPC, Flashbots characteristically intends to open-source the protocol in due time.

MEV Capture:

Another as-yet unconfirmed question is how matchmakers are compensated. My read of the current docs is that they are not paid via MEV—they simply receive searchers’ optimistically-built backrun bundles, and insert users’ transactions where called for therein. Though such private transactions could theoretically be their own, they have no chance to insert self-interested orders that pay them others’ MEV, like other BBPs. The fees paid to matchmakers sound more like the “network fees” discussed in Paradigm’s work on “base layer neutrality,” collected by neutral ISPs in exchange for shuttling packets around the Internet.

OFAC Risk:

Assuming the above is accurate, this intermediary actor appears to face lower risk. Unable to capture any MEV for itself, matchmakers may be seen to have no “control” over end users’ property. I’ll elaborate on this point in the context of relays below.

Beyond appearing relatively insulated itself, matchmakers also greatly help manage broader ecosystem risk by providing “programmable privacy” to the users of their OFA. Though not a trustless design, MEV-Share presents an interim alternative to fully shielded mempools, bringing threshold cryptography to the Flashbots Auction. At least within that popular environment, this could eliminate much MafiaEV and redistribute at least some MonarchEV, benefitting Ethereum as contemplated above.

OFAs also democratize access to user transactions, which reduces the centralizing forces that justify builders entrenching further with exclusive order flow. This opens the door for fairer execution of user preferences, as discussed more below.

Builders (and Sequencers)

Functions:

Without OFAs, builders today receive bundles from searchers and, often, additional private sources of raw user order flow (e.g., from “partnerships” with wallet providers and/or dark pools). They then run very computationally-intensive algorithms to organize, simulate and ultimately assemble the most profitable block to offer on to validators. The barrier to entry is high here—builders’ functions are very specialized and costly, typically necessitating data-center-scale deployments of processing power.

L2 sequencers fit in this category too, as a sequencer is effectively just a builder whose blocks come exclusively from order flow on the layer-2 blockchain it sequences. Presently, these functions are concerningly centralized across all leading L2s, though many intend to decentralize in the longer term. In the upcoming patch EIP-4844, a new “blob-carrying” transaction type will put sequencers in a preferential position, dramatically reducing gas costs to post L2 blocks to mainnet. This widens their margins, which they can spend on enticing validators to pick such blocks at market.

MEV Capture:

To the extent that the value is not forever lost to the Demon God of Coordination Failure, builders capture MolochEV by hyper-sorting orders they receive in ways that result in more capturable MEV than the inputs themselves contain. While builder decentralization is on Flashbots’s to-do list (more detail below), presently it is a trusted role, able to realize further 3EV by performing toxic searcher-like functions that, as Flashbots notes, “abuse privileged data access.” Sequencers also wield ultimate power over the contents of their L2s’ blocks, letting them draw MonarchEV from the system.

As with searchers, high competition for low-hanging fruit is causing builders to give away much of the MEV they manifest, in an effort to sell the most attractive block to choosy validators. Builders are hit even harder, though, as their suppressed revenues are strained by the high price of running their computers and the expensive R&D needed to move out on the long tail (seeking cross-domain MEV, etc.). Taken together, these dwindling profits create strong incentives for payment-for-order-flow deals and economies of scale, resulting in the builder centralization that Vitalik has presaged.

OFAC Risk:

As one of the other MEV-collecting BBPs, builders’ OFAC risk outlook is not too dissimilar from that of a searcher. In practice, their compliance practices would differ slightly, since builders are mostly fed third-party-generated bundles and transactions, rather than ferreting them out themselves. Instead of passively refusing to look for TC transactions to pass along, like searchers, they would have to more actively review the orders they receive from earlier BBPs and reject those that touch the SDN List.

The builder is an expected cornerstone of Ethereum’s architecture going forward, and accordingly many top minds are focused on achieving its openness and neutrality. Decentralizing the builder (examined next) and the sequencer unbundles these specialist jobs by—in true crypto style—introducing game theory to hopefully arrive at a fairer ordering of transactions (i.e., one with “0%” MolochEV). The transaction-shielding solutions detailed for earlier BBPs also prevent builders-as-searchers from enjoying the information asymmetries needed for MafiaEV, keeping it at “0%” too.

While L2s are outside current sanctions (as the TC addresses are on L1), this analysis is still pertinent to U.S. sequencers, as, in theory, anyone could spin up a TC fork on their chain and get sanctioned anew for similar North Korean activity. It is important that sequencers also think preventatively with respect to MEV and their neutrality.

As an alternative to the MEV marketplaces that Flashbots builds, some have outlined “fair ordering” protocols for confronting MolochEV, rejecting as a false premise the need for so-called “Frontrunning-as-a-Service.” Flashbots has since acknowledged the merits of such first-come-first-served (“FCFS”) ordering in stopping frontrunning (i.e., MafiaEV). Xinyuan Sun has gone further, proposing that Arbitrum—a layer-2 rollup that does not take part in the Flashbots Auction—adopt a “frequent batch auction” version of FCFS for its sequencer to further improve ordering efficiency and reduce spam (i.e., fight its own L2 MolochEV). Notably, some fair-ordering models have been disputed as unworkable on account of abstruse Ph.D.-level math.

Sub-Builder Executors

Functions:

Flashbots has codenamed its most ambitious gambit yet, “SUAVE”: a Single Unified Auction for Value Expression. As the full name implies, this new bespoke blockchain (still in its early research phases) will look to intermesh the functions of searchers and builders to achieve new synergies. The “preference environment” seen above acts as a rich, omni-chain mempool, where newly-anointed “executors” compete to provide users with optimal execution and ordering (i.e., with the least loss / MEV extracted).

If SUAVE is successful, it could combat the strong centralizing forces beset upon builders by distributing the sequencing compute and allowing participants of all sizes to share in cross-domain MEV. The project still carries many fundamental unknowns, including in its core design, whether as its own L1, a rollup, or even an EigenLayer restaking contract. With such large variables outstanding, much of executors’ place in this landscape depends on hopes for engineering that remains to be fleshed out.

MEV Capture:

A key question that needs to be answered is whether executors still sit in a privileged position over the flows they facilitate. If this further sub-market just pushes the builders’ MEV one level deeper, to these humans, is it “turtles all the way down”?

Sun postulates that we could eliminate MolochEV by increasing overall coordination efficiency with this specialized marketplace, creating a virtuous race to the bottom (see, “Minimizes MEV” in the diagram above). A fully-realized SUAVE would also quash MafiaEV within its borders, using the programmable-privacy mechanisms first beta-tested in MEV-Share. Per the diagram, MEV-Share and other OFAs seemingly could slot into SUAVE’s execution market as well, returning remaining MonarchEV to end users, and completing 3EV’s “0% / 0% / 100%” vision.

OFAC Risk:

SUAVE represents just one path to actualizating much of the theory that Sun and his colleagues discuss around achieving Ethereum’s credible neutrality, yet it is the most cohesive I’ve seen presented to date. There are likely years of R&D left to bring this magnum opus to mainnet—in the meantime, centralized BBPs of all types will be left to piece together the benefits it promises from the other solutions mentioned herein.

Whether thanks to a consolidated product like SUAVE or some amalgamation of other offerings, reaching a state that arguably resembles “0% / 0% / 100%” will be the first step in a longer process to establish a regulatory consensus for BBPs that understands, respects and enshrines their functions. But, as with much of the legal bushwhacking that this industry has endured or must encounter going forward, the only way out is through.

Relays

Functions:

Relays, unlike BBPs elsewhere in the chain, don’t really have a business model. They might be better thought of as public goods, needed to prevent feared game-theoretic breakdowns in coordination between the now-separated builders and proposers.

Relays receive full blocks from builders, but instead of performing any additional complex transformations upon them, they simply verify the blocks’ contents as valid or otherwise acceptable (read, not subjecting their operators to excessive risk of criminal prosecution). They then pass along the blocks’ headers—only their metadata, not their contents—to inquiring validators. Once a validator commits to proposing a relay’s block, only then does it pass it along in full.

Effectively acting as escrow agents, relays prevent “griefing” among the disinterested BBPs with which they interact. However, such parties must trust this currently-centralized actor not to alter their block (e.g., by filtering transactions out of it).

MEV Capture:

Interestingly, in the Flashbots Auction, relays do not take any share of MEV—this ties into how MEV is actually paid by earlier BBPs to validators, per the above. When searchers create bundles and builders then make them into blocks, any MEV that they do not retain is promised directly to the proposing validator’s coinbase through a transaction appended to the end of such bundle / block, bypassing the relay entirely.

By not participating in the specialized functions that identify MEV and extract that value through order-flow manipulation, relays are not in the position to add in their own transactions that would make them money. They thus go unpaid for their services.

OFAC Risk:

As an actor that truly only deals in information and not any economic interest in the property attendant thereto, relays look much more like the platonic ideal of a BBP: one that performs lower-risk, “purely clerical” duties. Any OFAC risk that this piece attributes to MEV seems not to apply to the relay, which arguably lacks that necessary element of “control” over the sanctioned property being transacted in.

Relieved of much of the concern discussed above, those operating relays are freer to make a political stand, that under a functionalist conceptualization, relays truly are neutral messengers akin to those in other industries. This posture might include just not censoring. It would certainly be a riskier endeavor, but if/when the industry is ready to press the issue, running an uncensored U.S. relay could be an impactful way to push the government to take the policy arguments herein seriously. Given that relays are generally operated altruistically, they present an opportunity for a monied champion to secure a serious point in the “win” column for the industry.

Politically-minded relays may find it useful to draw an analogy to an existing actor that facilitates financial messaging within the United States. The Clearing House Payments Company, L.L.C., a DE LLC, operates the Clearing House Interbank Payments System (“CHIPS”), which processes U.S. dollar transfers made among international banks. Unlike the SWIFT network (and similar to the Ethereum network), CHIPS settles such transfers in real time; it doesn’t just send messages around for others to settle. To my knowledge, neither CHIPS nor the U.S. entity running it are subject to KYC, monitoring or filtering duties imposed by OFAC. This rabbit hole probably deserves its own dedicated article to explore as well.

Alas, this relay is not long for this world. A key part of The Scourge—Ethereum’s big multi-part, MEV-aware update, timing TBD—is implementing so-called “Enshrined” or “In-Protocol” Proposer-Builder Separation (“PBS”). This feature set would subsume relays’ escrow functions within the protocol itself and render trusted third parties obsolete here. But, unlike many advancements previewed above, Enshrined PBS is still very much a research question. It could take much longer to land on mainnet than insiders’ more optimistic forecasts (see, The Merge), so there is likely still time to use the relay politically, if the space musters the will to do so. In the meantime, the encryption solutions above would help prevent any abuse by centralized relays, shifting them into the same “Can’t Be Evil” position as other BBPs.

Validators / Proposers

Functions:

The validator sits at the end of the block-building line, and is the BBP that interfaces with the Ethereum network itself. Validators perform multiple jobs in order to ensure that valid blocks land on-chain (e.g., attestation to the validity of blocks added by other validators). In speaking about the Flashbots Auction, it is most precise to refer to these actors by their function, as “proposers,” since that is the job they perform in that context. When randomly selected pursuant to Ethereum’s Proof of Stake protocol, they have the opportunity to propose a new block for inclusion.

Prior to The Merge, Ethereum miners built their own blocks, and won the chance to propose them by besting the Proof of Work protocol’s hashing game. When MEV was first broadly exposed by Daian et al., these consolidated functions were resulting in some of the same market failures with miners that plague TradFi institutions today, as noted above. This gave rise to Ethereum’s quest to vanquish MEV as a means of achieving credible neutrality, including through PBS designs. The Flashbots Auction represents Ethereum’s first attempt to actualize PBS, though it exists “out-of-protocol,” made available to vanilla Ethereum validators through a Flashbots sidecar called MEV-Boost. Validators can point their Builder APIs to MEV-Boost, outsourcing their default obligations to build such blocks locally.

MEV Capture:

Since the relay doesn’t share the contents of its block with a proposer until after the proposer has firmly committed to proposing such block, proposers are unable to conduct any manipulation thereupon without incurring slashing penalties from the protocol. This is a core design goal of PBS: to shift those privileges to other BBPs, where they can better be neutralized, as discussed above. In other words, thanks to PBS, validators-as-proposers are no longer able to directly extract MafiaEV. Though proposers still end up enjoying payments of this 3EV, as detailed above, by isolating its production in specialist BBPs, PBS allows for its targeting, commoditization and hypothetical ultimate elimination.

The outstanding research questions around proposers’ 3EV then turn to MonarchEV. The term—used as a bit of a catch-all for flavors of MEV that don’t cleanly fit into the other two buckets—helpfully points to how there is always a final authority on what information gets included in a given block, but it doesn’t provide as clear of a solution for resolving its negative impact. Sun seems to concede that some MEV is always going to exist in saying that MonarchEV should be paid back to users and not kept by BBPs. It remains an open issue how to trustlessly effect that retransfer of value, and whether the proportion that can be repaid will come close to 3EV’s aim of “100%.”

It should be noted that, due to the delays in propagation that TC transactions suffer due to current weak censorship, some TC users opt to tip validators extra “priority fees” (enabled by EIP-1559) to include their transactions locally in the proposed block, before other users only paying lower base-gas rates. Like the fees envisioned for matchmakers above, these priority fees are more analogous to telecom and ISP service fees, and do not implicate the legal and policy concerns that the predatory practices surrounding toxic MEV do.

OFAC Risk:

Since blocks are shielded from the validator pre-proposal, validators’ status quo policy argument is a bit different than other BBPs, who can monitor block contents before making any binding commitments. By using MEV-Boost with its default settings, proposers act in an economically rational manner, strictly picking the most profitable block offered across all available relays. Their neutrality is not challengeable by any assertion that they have competing motivations, balancing maximizing profit with, say, pursuing a political agenda (e.g., “promoting censorship resistance”). The less subjectivity that proposers exercise over their block selection, the better policy arguments they can make here. This naturally implies that validators that wish to be viewed as credibly neutral should not affirmatively build TC-laden local blocks (even through the use of MEV-Boost’s updated “min-bid” feature).

This deduction, however, seems to conflict with one of the other key elements of The Scourge: so-called “inclusion lists.” Such lists would re-empower proposers with a degree of subjectivity, letting them make demands of builders that they will not agree to propose any block that doesn’t include certain orders (e.g., TC transactions). I understand that the core devs are mindful of this tension. Some are considering “canonical” inclusion list designs, where the list is somehow made non-optional for the proposer itself, presumably constructed in-protocol away from the validator. While arguably beneficial to remove this degree of choice from the individual validator, I have lingering concerns that this could shift the risk to the network writ-large, rendering the potential downside more catastrophic. The community will have to consider seriously whether the network is ready and able to bear that weight.

Should Ethereum move forward with inclusion lists, as is currently contemplated, it will also want to ensure that the protocol is as fair and fortified as possible. In addition to the 3EV-fighting mechanisms detailed above, there has also been promising research conducted with respect to MEV-burning and/or smoothing mechanisms, like auctions where validators bid to sacrifice their MEV in exchange for the right to a block. Others have posited that some amount of validator MEV (i.e., that which cannot optimally be returned back to users) could be understood as ecosystem-beneficial, as it encourages continued staking and thus network security. And finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t give a nod to advances in Distributed Validator Technology, which seeks to decentralize the validator itself, entrenching the core tech further and making it more difficult for authorities to enforce against any single actor.

N.B.: Pool operators have been rendered obsolete on Ethereum by The Merge, though Ethermine—the then-largest U.S. Ethereum PoW pool—stopped mining transactions from TC immediately after the dApp’s addition to the SDN List.

So, we’re getting there—Ethereum continues to grow, along both its protocol and social dimensions. In time, if/when most toxic MEV has been rendered uncapturable or cured through coordination, we will have firmer policy footing to contend that the chain and its remaining MonarchEV—largely returned to users via MEV-sharing OFAs or otherwise burnt—foster a financial-messaging system comparable to or better than that available on Wall Street. Meanwhile, as the Ethereum Foundation, Flashbots and their peers work to alleviate the protocol’s shortcomings (and harden it against enforcement), each BBP has a legal responsibility to understand and manage its evolving risk profile. For an incipient industry with little yet to say for best practices, a few action items:

Seek counsel about your particular situation—unless we’ve agreed, I’m not yours;

Realize risk runs on a spectrum and, absent shutting down, yours won’t be at 0;

Record everything the organization does to seek and maintain compliance (e.g., in meeting minutes, employee-acknowledged policies and procedures, tailored legal analyses, a tweet on how much you learned from this piece, etc.); and

Engage in the vigorous policy advocacy needed to present crypto in a more serious light, whereby BBPs—neutered by the tech itself—may be embraced as a net-positive for this next generation of finance, rather than its outsized liability.

Barbarians at Whose Gate?

That said, if we're rightfully seeking to educate lawmakers on this technology, then we shouldn't be caught off-guard if they eventually grasp how it all works, but still come to reproachful conclusions. A slogan like, “regulate apps, not protocols” could serve as arguably-useful rhetorical shorthand for the notions of credible neutrality discussed here and elsewhere. If pursued literally, though, the line not only misses the self-serving humans running businesses “on the base layer,” but also presumes a horse trade that has not as yet been offered or accepted by the U.S. government. Satoshi said that his innovation was political, and it would be a disservice to crypto if we didn’t stay adversarially aware here.

It appears one of crypto’s most outspoken critics, Senator Elizabeth Warren, is already receiving competent advice on the existence and functions of BBPs. In a recent piece of draft legislation, she took the opportunity to call out “validators, or other nodes who may act to validate or secure third-party transactions, independent network participants, including MEV searchers, and other validators with control over network protocols” as exceptional targets for money-service-business (“MSB”) regulation.

With an MSB classification, U.S. BBPs would be burdened with much more direct, affirmative OFAC-compliance obligations. This would effectively impose full BBP KYC—an impracticability in most instances on Ethereum—going beyond liability merely imputed through “facilitation,” as discussed above. While Warren’s first volley went nowhere in the Senate, I understand that she is making a credible pass at moving this bill again, now with bipartisan co-sponsors, drumming up support for her “Anti-Crypto Army” as pro-crypto sentiment crabs near its local lows.

Our industry is, appropriately, keenly focused on protocol design and engineering. Given Ethereum’s goal of being a global settlement layer (i.e., operating in highly controlled spaces), however, it is critical that we don’t ignore the need for legal design and engineering in parallel, else we could spend years engaged in a hamstrung campaign that does not comport with the world-hegemon’s realpolitik.

Deftly Preempting My Haters

The unwashed critic might ask, e.g., “Aren’t you worried about ‘leaving breadcrumbs’? If there’s a race on between the growingly-less-ignorant regulators and devs-doing-something, why are you snitching now? Isn’t it smarter to be silent?,” to which I would reply (wisely), being an ostrich is not a strategy. OFAC experts will tell you: act in good faith, and document your compliance in real time. In that way, this essay is literally helping BBPs avoid penalties, right now.

It’s crucial that we take these prophylactic measures, since we won’t be able to delay the (imho) inevitable forever. Beyond OFAC’s and Warren’s awareness noted above, state legislators (like those in Illinois) are also being briefed on BBPs. Without strong industry engagement in the political process, those in power will only be guided by those outside of our true-believer bubble and will remain unlikely to pass any laws we’d support. We need to face these inconvenient truths head-on and hands-on.

This is not some revolutionary new perspective, either. Indeed, Flashbots, Coinbase and others are already acting in line with the viewpoints expressed here. Though they are being even more cautious in some cases (see, Flashbots’s relay), they’re aptly aggressive in others (e.g., Coinbase’s posturing that it will defend staking in court). The value-add here is in setting forth a replicable—not reactive—framework for thinking about BBPs in the public discourse, employing honest functionalism, because our governors are not impressed with our fancy formalist footwork. Otherwise, any coherent modeling may remain buried in the ToS, quarterly reports and/or privileged work-product of market leaders, if contemplated at all.

It is also curious that the industry wasn’t up in arms about U.S. BBPs conducting SDN-filtering prior to the TC sanctions, though Flashbots and others already had such procedures in place to comply with OFAC (e.g., Flashbots’s exclusion of Lazarus EOAs, as noted above). Do people’s reactions reflect concern only about the new broader scale of OFAC’s reach, spurred by what some saw as overreactions by actors on the “application layer” who blocked users multiple “hops” away from a direct TC interactions, along with the high-profile dusting attacks that followed?

If this is a concern over the magnitude of censorship rather than the existence of it, one may find it humorous that all of this brain damage is being done over a thirty-second delay for a few hundred TC transactions per week. If not, and commentators insist that the fight for “censorship resistance” is a broad mandate, no matter what addresses are being weakly censored, they should earnestly examine whether they would be willing to hold that same ideological line with respect to other North Korean, Russian and allied (e.g., Chinese, Pakistani) EOAs, where there are arguably the same hard questions for BBPs.

This piece raises plausible interpretations and their implications. It seeks truth with a “strong opinions, weakly held” mindset. I have frequent vigorous debates with friends and colleagues on these issues (and welcome any more, DM me), but one cannot deny that there’s enough here to pull the thread. This corner of the industry is still so young that facts and circumstances will evolve substantially over time, i.e., as the tech I flag above ships—fittingly, so will my legal takes.

A Note on the Endgame

The above legal / ops material (i.e., the arbitrary U.S. censorship) is, ideally, temporary, as Ethereum’s neutrality and resiliency compound and the network turns to dust. The Ethereum Foundation is not worried about the chain’s long-term survival, and neither am I—weak censorship is FUD, and “the base layer” is the most robust part of the blockchain stack, by design. Even if “strong censorship” (i.e., a government-compelled/conducted 51% attack) were to occur, Ethereum (and with it, TC) is likely to persist for so long as the Internet does. The former will continue to adapt to the world it serves as long as its community cares enough to fight for it.

Maybe it’ll all go this way; who knows? There’s also a world where, for example, (i) the industry adopts an “OFAC-compliant” TC fork for privacy, (ii) TC’s liquidity dries up thanks to good-old-fashioned competition, and (iii) there is therefore no need under current law for material censorship on Ethereum, thankfully rendering my work moot. Whatever the future holds, the purpose of this essay is to spread awareness of the facts as they stand so that BBPs and their advisors and advocates can go forward clear-eyed (and not blinded by rainbows and unicorns).

OFAC sanctions are not the only legal issue that the burgeoning BBP sector faces—from fiduciary and other duties, to data privacy, market manipulation, consumer protection, MSBs, extra-Howey securities (ATS, broker-dealer, transfer agent, etc.), antitrust and even general corporate considerations (e.g., structuring and tax). I look forward to discussing those, and any other #MEVlaw questions anyone may have, in future writings. 🏄🏼♂️⚡️

Sincere thanks to Mikolaj Barczentewicz, Sarah Brennan, Justin Drake, Michael Mosier, Rodrigo Seira, Eric Siu and Gabriel Shapiro for their input and insight throughout the preparation of this piece, and to all of the brilliant researchers that I’ve linked to throughout.

Credit to the Midjourney Bot on Discord for the heading-prompted artwork.

NOTE: Subject to change without notice. None of the foregoing shall be construed as legal, financial or other advice of any kind. Please review certain further disclosures concerning autonomous lawyering, found here. Do your own research. For further information, visit:

A one-page summary of the technical and policy matters detailed in this essay is available for download, here.

FURTHER EXAMPLES OF TOXIC MEV:

The exceedingly exotic fare devised by the mempool’s uncle bandits, who have cleverly exploited other searchers’ attempted sandwich and other botting bundles within uncle blocks (i.e., blocks that failed to reach the blockchain because they were created at roughly the same time as different, chosen blocks). At first glance, these exploiters appear to have done the impossible: split up another searcher’s bundle. However, since uncled transactions never settle on-chain, these bandits are able to pluck out only a portion of the exploited bundle (e.g., the frontrun-buy of an attempted sandwich), scrap the rest, and instead arbitrage the relevant price back down, or even sandwich the retained buy transaction themselves; and

The potentially cataclysmic time-bandit attack first theorized by Daian et al. in their seminal work, Flash Boys 2.0, wherein the authors (led by a future co-founder of Flashbots) first calculated that it could be profitable to pursue a chain reorg on Ethereum in order to steal MEV already captured by other BBPs in past blocks. This most extreme form of MEV effectively proved a dreaded 51% attack to be economically rational, and as a result cast MEV as the technological archenemy of the ecosystem which must be defeated for the blockchain to last.

![War... war never [ch/or]anges. War... war never [ch/or]anges.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!eE8W!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8408b38a-4470-482b-bf61-65cb3cfe28a9_1024x1024.png)